Electronic cigarettes equally effective as patches in helping to quit smoking

Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial.

Literature - Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M et al. - Lancet. 2013 Sep 9. [Epub ahead of print]Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M et al.

Lancet. 2013 Sep 9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5. [Epub ahead of print]

Background

Many smokers use electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) to try and quit smoking, although the place of e-cigarettes in tobacco control is controversial [1,2]. Evidence suggests that e-cigarettes have the potential to help smokers in quitting or reducing to smoke, and that they can deliver nicotine into the blood stream, thereby attenuating tobacco withdrawal as effectively as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) [3,4]. However, a trial in 300 smokers unwilling to quit only showed low rates of cessation after 12 months of use of nicotine and placebo e-cigarettes [5]. Furthermore, toxins have been detected in e-cigarette fluid and vapour [6], although at the about the same concentration as with NRT, and lower than in cigarette smoke.This randomised trial was set up to assess whether e-cigarettes with cartridges containing nicotine were more effective for smoking cessation than nicotine patches, and included a blind comparison with e-cigarettes containing no nicotine (placebo e-cigarette). 657 People who wanted to quit smoking were randomised to nicotine e-cigarettes, patches or placebo e-cigarettes in a 4:4:1 ratio.

Main results

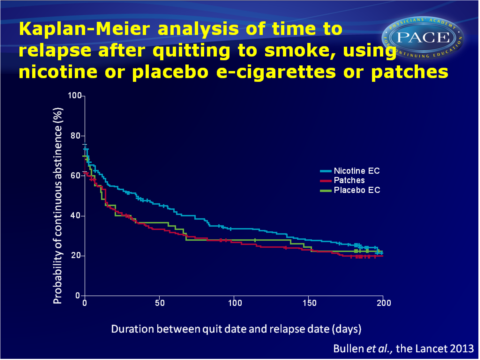

- Verified continuous abstinence at 6 months after quit day was highest in the nicotine e-cigarettes group (7.3%), followed by the patches group (5.8%) and lowest in the placebo group (4.1%). Statistical power was not sufficient to conclude superiority of nicotine e-cigarettes over patches or placebo, due to unexpected low success rate of abstinence.

- Quit rates were initially high, and non-significantly in favour of nicotine e-cigarettes, and then decreased in all groups. Most participants relapsed within 50 days (median time for nicotine e-cigarettes: 35 days, 95%CI: 15-56, as opposed to 14 days (95%CI: 8-18, P<0.0001) with patches or 12 days (95%CI: 5-34, P=0.09) with placebo e-cigarettes.

- Mean cigarette consumption decreased by two cigarettes per day more in the nicotine e-cigarettes group than in the patches group.

- Stage of addiction according to the autonomy over smoking scale (AUTOS) was measured after 6 months. AUTOS scores were halved in the e-cigarettes groups as compared to a decrease of a third in the patches group. No statistically significant difference was seen between use of nicotine vs. placebo e-cigarettes.

- More adverse events were seen in the nicotine e-cigarettes group than in the patches group, but there was no evidence of an association with study product, and event rates did not differ significantly.

- Adherence to study treatments was significantly higher in the nicotine and placebo e-cigarettes group than in the patches group (P<0.001 at each follow up assessment).

- Among those using nicotine e-cigarettes with verified abstinence, 38% were still using the e-cigarettes at 6 months, as opposed to 29% of the non-quitters.

- Quitline support was accessed by fewer than half of participants in all groups. Post hoc analysis showed no benefit of use of support for abstinence.

Conclusion

E-cigarettes with or without nicotine were modestly effective in helping smokers to quit. Non-significant differences were seen between nicotine e-cigarettes and use of patches or placebo e-cigarettes, favouring nicotine e-cigarettes across a range of analyses. Nicotine e-cigarettes appear at least as effective as patches for smokers wanting to quite. Since this study showed a higher acceptability of e-cigarettes over patches among smokers, and no greater risk of adverse effect, e-cigarettes seem to have potential for improving population health.This study was underpowered to be able to detect the role of behavioural replacement with e-cigarettes in cessation, independent of nicotine delivery.

Download Bullen 2013 PACE.pptxor click to enlarge

References

1. Hajek P, Foulds J, Houezec JL, et al. Should e-cigarettes be regulated as a medicinal device? Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 429–31.

2. Cobb N, Cobb C. Regulatory challenges for refined nicotine products. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 431–33.

3. Bullen C, McRobbie H, Thornley S, et al. Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e cigarette) on desire

to smoke and withdrawal, user preferences and nicotine delivery: randomised cross-over trial. Tob Control 2010; 19: 98–103.

4. Vansickel A, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes: effective nicotine delivery after acute administration. Nicotine Tob Res 2013; 15: 267–70.

5. Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Cibella F, et al. Efficiency and safety of an electronic cigarette (ECLAT) as tobacco cigarettes substitute: a prospective 12-month randomized control design study. PloS One 2013; 8: e66317.

6 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Summary of results: laboratory analysis of electronic cigarettes conducted by FDA. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ucm173146.htm (accessed Aug 9, 2013).

Facebook Comments