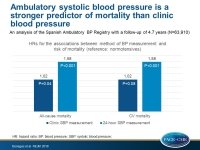

Ambulatory BP stronger predictor of mortality than clinic BP

24-hour, daytime, and nighttime ambulatory systolic blood pressure measurements were better predictors of all-cause and CV mortality compared with blood pressure measurements in the clinic.

Relationship between Clinic and Ambulatory Blood-Pressure Measurements and MortalityLiterature - Banegas JR, Ruilope LM, de la Sierra A, et al. - N Engl J Med 2018;378:1509-20.

Introduction and methods

Ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) data predict more accurately health outcomes compared with blood pressure (BP) measured in the clinic or at home, based on studies with limited clinical outcomes, but it is not clear which measures exactly (daytime vs. nighttime vs. 24-hour measurements) and the implications of hypertension phenotypes, e.g. ‘white-coat’ (elevated clinic BP and normal 24-hour ABP) or masked hypertension (normal clinic BP and elevated 24-hour ABP), with regard to mortality are not well known [1,2].

In this analysis of the Spanish Ambulatory Blood Pressure Registry, the prognostic value of clinic and ambulatory BP, as well as of hypertension phenotypes, was evaluated on total and CV mortality in a large cohort of patients in primary care practice. The Spanish Ambulatory Blood Pressure Registry includes 66,636 individuals aged ≥18 years with guideline-recommended indications for ambulatory BP monitoring, enrolled between 2004 and 2014 [3,4]. Of these, 2,726 were excluded because of incomplete information on demographic or clinical characteristics, leaving a sample size of 63,910 patients for the analysis.

BP was measured in the clinic according to standardized procedures, with the use of validated devices, after the patient had been resting in a seated position for 5 minutes. The mean of two clinic BP readings was used. ABP monitoring was performed with validated, automated, oscillometric devices that were programmed to record BP at 20-minute intervals during the day and at 30-minute intervals during the night. The date and cause of death were ascertained from a computerized search of the registry of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics. The median follow-up was 4.7 years.

Main results

After full adjustment, the associations of systolic BP measurements and all-cause mortality were:

- HR for clinic BP: 1.02 (95%CI: 1.00-1.04; P=0.04)

- HR for 24-hours ABP: 1.58 (95%CI: 1.56-1.60; P<0.001)

- HR for daytime ABP: 1.54 (95%CI: 1.52-1.56; P<0.001)

- HR for nighttime ABP: 1.55 (95%CI: 1.53-1.57; P<0.001)

After full adjustment, the associations of systolic BP measurements and CV mortality were:

- HR for clinic BP: 1.02 (95%CI: 1.00-1.04; P=0.08)

- HR for 24-hours ABP: 1.58 (95%CI: 1.55-1.60; P<0.001)

- HR for daytime ABP: 1.54 (95%CI: 1.52-1.57; P<0.001)

- HR for nighttime ABP: 1.56 (95%CI: 1.53-1.59; P<0.001)

After full adjustment, the associations of different hypertension phenotypes with all-cause mortality were:

- HR for white-coat hypertension: 1.79 (95%CI: 1.38-2.32; P<0.001)

- HR for masked hypertension: 2.83 (95%CI: 2.12-3.79; P<0.001)

- HR for sustained hypertension: 1.80 (95%CI: 1.41-2.31; P<0.001)

After full adjustment, the associations of different hypertension phenotypes with CV mortality were:

- HR for white-coat hypertension: 1.96 (95%CI: 1.22-3.15; P=0.005)

- HR for masked hypertension: 2.85 (95%CI: 1.66-4.90; P<0.001)

- HR for sustained hypertension: 1.94 (95%CI: 1.23-3.07; P=0.005)

Conclusion

In a large registry analysis, 24-hour, daytime, and nighttime ambulatory systolic BP were all better predictors of all-cause and CV mortality compared with clinic BP. White-coat hypertension was not benign and the BP phenotype with the highest risk of death was masked hypertension.

Editorial comment

In his editorial article, Townsend [5] summarizes the results published by Bonegas et al, and concludes: ‘The take-home message from this study is that ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring is a valuable tool in the assessment of the most important and treatable factor worldwide contributing to premature death and disability, namely, blood pressure. The ominous effect of white-coat hypertension has been noted by others, and it is probably related to the increasing magnitude (i.e., the difference between clinic blood pressure and ambulatory blood pressure) of white-coat hypertension with age. It is hoped that the work of Banegas et al. will serve as one more spur to manufacturers of ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring devices and to providers in this field (like this author) to initiate a registry in the United States.’

References

1. Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 2368-74.

2. Mancia G, Verdecchia P. Clinical value of ambulatory blood pressure: evidence and limits. Circ Res 2015; 116: 1034-45.

3. Gorostidi M, Banegas JR, de la Sierra A, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in daily clinical practice — the Spanish ABPM Registry experience. Eur J Clin Invest 2016; 46: 92-8.

4. O’Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, et al. European Society of Hypertension recommendations for conventional, ambulatory and home blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 821-48.

5. Townsend RR. The Value in an Ambulatory Blood-Pressure Registry. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1555-56.