Cardiovascular effects of smoking and smoke-free legislation

08/11/2012

Lancet, BMJ, Circulation, JAMA nov 2012 . 4 new studies give powerful evidence of the cardiovascular risk of smoking and the health benefits of quitting or not being exposed to secondhand smoke.

Four new studies give powerful evidence of the cardiovascular risk of smoking and the health benefits of quitting or not being exposed to secondhand smoke.Literature - Lancet, BMJ, Circulation, JAMA October 2012

Smoking in the UK [1]

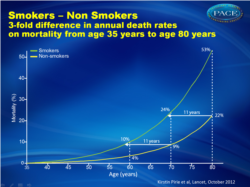

Between 1996 and 2001 the Million Women Study started following more than one million women aged 50 to 65 years of age. The study showed that 12-year mortality was significantly higher in women with a history of smoking compared to women who never smoked (rate ratio 2.76, CI 2.71-2.81). Smokers lose 10 years of life. The good news is that stopping smoking before the age of 40 reduces the excess mortality by 90%.

Smoking in Japan [2]

The Life Span Study was started in 1950 and followed more than 65,000 men and women in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. The results were consistent with the Million Women Study in the UK: the rate ratio for mortality was more than doubled for smokers compared to nonsmokers both for men (2.21, CI 1.97-2.48) and for women (2.61, CI 1.98-3.44). Stopping smoking before age 35 eliminated almost all of the risk associated with smoking.

Smoke-free legislation meta-analysis [3]

Smoking is not just a personal decision that has individual health effects. A new meta-analysis showed that smoke-free legislation results in immediate reductions in hospital admissions or deaths for coronary events (RR .848, CI .816-.881), other heart disease (RR .610, CI .440-.847), cerebrovascular accidents (RR .840, CI .753-.936) and respiratory disease (RR .760, CI .682-.846). The biggest reductions in events were associated with the most stringent smoke-free laws.

Smoke-free legislation in Minnesota [4]

A fourth study analyzed data before and after the implementation of a smoke-free law in Olmsted County, Minnesota. A significant 33% reduction was found in the incidence of MI from 150.8 to 100.7 per 100000 people and a trend in the reduction of sudden cardiac death by 17% from 109.1 to 92.0 per 100,000 people. In an accompanying commentary [5], Sara Kalkhoran and Pamela Ling write that as “the evidence base documenting the positive health outcomes” of smoke-free legislation grows, “we should prioritize the enforcement of smoke-free policies.”

References

1. Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, et al; for the Million Women Study Collaborators. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2012 Oct 26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6. [Epub]2. Sakata R, McGale P, Grant EJ, et al. Impact of smoking on mortality and life expectancy in Japanese smokers: a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012 Oct 25;345:e7093. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7093.

3. Tan CE, Glantz SA. Association between smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for cardiac, cerebrovascular, and respiratory diseases: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2012;126:2177-83.

4. Hurt RD, Weston SA, Ebbert JO, et al. Myocardial Infarction and Sudden Cardiac Death in Olmsted County, Minnesota, Before and After Smoke-Free Workplace Laws. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.46. [Epub]

5. Kalkhoran S, Ling PM. Extending the Health Benefits of Clean Indoor Air Policies. Arch Intern Med. 2012. doi:10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.269