CVD mortality risk increases with sugar intake

For most American adults the amount of calories derived from added sugar is higher than recommended. This is associated with increased risk of CVD death.

Added Sugar Intake and Cardiovascular Diseases Mortality Among US AdultsLiterature - Yang Q et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 - JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Feb 3

Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, et al.

JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Feb 3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13563.

Background

Average consumption of added sugar, including sugar added in processing or preparing food, increased from 235 calories per day in 1977-1978 to 318 calories per day in 1994-1996 [1]. Between 1999-2000 and 2007-2008, the absolute and percentage of daily calories derived from sugars declined, but consumption remained high [2]. The Institute of Medicine recommends that consumption of added sugar does not exceed 25% of total calories [3], while the World Health Organization recommends less than 10% [4].Evidence exists that individuals who consume higher amounts of added sugar, especially sugar-sweetened beverages, tend to gain more weight and have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease [5,6] and associated risk factors. No studies have investigated total added sugar, in nationally representative samples. This study examines time trends of consumption of added sugar as percentage of total daily calories using a series of national representative samples. The association of this consumption with CVD mortality was investigated in the prospective National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cohort [7,8].

Main results

- The mean percentage of calories from added sugar increased from 15.7% (95% CI: 15.0-16.4) in 1988-1994 to 16.8% (95% CI: 16.0-17.7, P <0 .02) in 1999-2004 and decreased to 14.9% (95% CI: 14.2-15.5, P <0 .001) in 2005-2010. 71.4% of adults consumed at least 10% of calories from added sugar, and for about 10% this percentage was at least 25%.

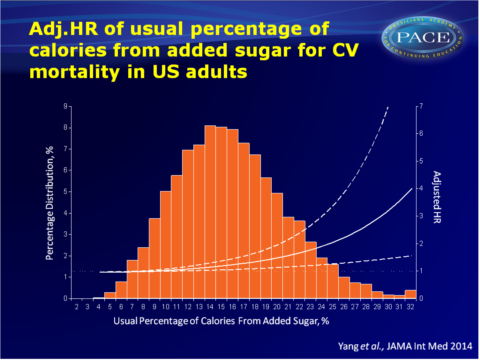

- Risk of CV death increased with ascending sugar intake. When comparing those who consumed 10-24.9% or at least 25% of calories from added sugar with those who consumed less than 10% of calories from added sugar, adjusted HRs were 1.30 (95% CI: 1.09-1.55) and 2.75 (95% CI: 1.40-5.42).

- The number needed to harm (NNH) of CVD mortality at 15 years of follow-up dropped substantially with decreasing quintiles of sugar consumption (from 265 (95%CI: 166-715) in the second quintile to 22 (95%CI: 13-66) in the highest quintile).

- The observed association between percentage of calories from added sugar and CVD mortality risk was largely consistent across groups based on age, sex, ethnicity, educational attainment, physical activity level, Healthy Eating Index (HEI) score and BMI.

- Adjustment for each component of the HEI score did not affect HRs for CVD mortality. A significant association was seen when comparing those who consumed at least 7 sugar sweetened drinks (360 mL/serving) per week to those who consumed 1 serving or less per week (HR: 1.29, 95%CI: 1.04-1.60).

Download Yang jama 2014 pace.pptx

Conclusion

The vast majority of American adults derived at least 10% of their total calorie-intake from added sugar, and for about 10% of adults this percentage was at least 25%. Thus, sugar consumption of most adults is more than what is recommended for a healthy diet. Increased consumption of calories from added sugar is associated with increased risk of CVD mortality.Correction for HEI score and its individual components suggests that the association between added sugar intake and CVD mortality was not explained by overall diet quality. Regular consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is, however, associated with increased CVD mortality risk. These results underscore current recommendations to limit the intake of calories from added sugars.

Editorial comment [7]

We are in the midst of a paradigm shift: while overconsumption of sugars was previously assumed to reflect an unhealthy diet or obesity, sugar overconsumption is now seen as an independent risk factor in CVD and other chronic diseases. Indeed this study suggests that at levels of consumption common among Americans, added sugar is a significant risk factor for CVD mortality above and beyond its role as empty calories leading to weight gain and obesity. However, in contrast to sodium, trans fats, and other dietary additives used to increase the palatability and shelf life of processed foods, the US government provides no dietary limit for added sugar. This study underscores the appropriateness of evidence-based sugar regulations, specifically, taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages. This study furthermore documents rates of heavy sugar consumption among blacks nearly double those of whites, reaffirming the need for a national strategy to address inequities in food access.Find this article on Pubmed

References

1. Popkin BM, Nielsen SJ. The sweetening of the world’s diet. Obes Res. 2003;11(11):1325-1332.

2. Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Chomitz VR, et al. A randomized trial of sugar-sweetened beverages and adolescent body weight. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(15):1407-1416.

3. Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Macronutrients. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids.Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005.

4. Nishida C, Uauy R, Kumanyika S, et al. The joint WHO/FAO expert consultation on diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: process, product and policy implications. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(1A):245-250.

5. Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121(11):1356-1364.

6. de Koning L, Malik VS, Kellogg MD, et al. Sweetened beverage consumption, incident coronary heart disease, and biomarkers of risk in men. Circulation. 2012;125(14):1735-1741.

7. Schmidt LA. New Unsweetened Truths about Sugar. JAMA Internal Medicine Published online February 3, 2014