Exercise reduces CVD-related mortality in hypertensives

Provided the energy expenditure is the same, walking and running yield similar risk reductions, but current exercise guidelines are inadequate to reduce CVD mortality.

Walking and running produce similar reductions in cause-specific disease mortality in hypertensivesLiterature - Williams PT - Hypertension. 2013 Sep;62(3):485-91

Williams PT

Hypertension. 2013 Sep;62(3):485-91. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01608

Background

Physical activity lowers the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality, in normotensives and hypertensives [1]. Many aspects of the beneficial effect of physical activity for hypertensives remain unclear, such as whether a dose-response relationship exists, the effect of intensity and the specific diseases affected. Previous cohorts provided little insight into the optimum exercise dose, because they were set up for general purposes, thus did not include very detailed quantification of activities. None of the studies compared the benefits of moderate versus vigorous exercise.The National Runners’ and Walkers’ Health Studies [2-10] are the only large prospective cohort designed to specifically assess the health benefits of exercise. Data of over 10000 hypertensive medication users (6973 walkers and 3907 runners) were analysed to investigate the nature of the dose-response relationship between exercise and mortality and whether it affects specific CVD diagnoses, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Main results

- Hypertensives were at higher risk for all-cause mortality than normotensives (30.5% higher, 95%CI: 21.0-40.8%, P<0.001), as well as for mortality related to CVD (47.5% higher, 95%CI: 33.5-62.8%, P<0.001) (adjusted).

- Meeting the current exercise guidelines (1.07-1.8 METh/d) gave a non-significant risk reduction of all-cause mortality by 9%, as compared to not meeting them (<1.07 METh/d). When guidelines were exceeded 1-2 fold (1.8-3.6 METh/d), all-cause mortality decreased by 29%. Energy expenditure >3.6METh/d did not seem to further reduce all-cause mortality.

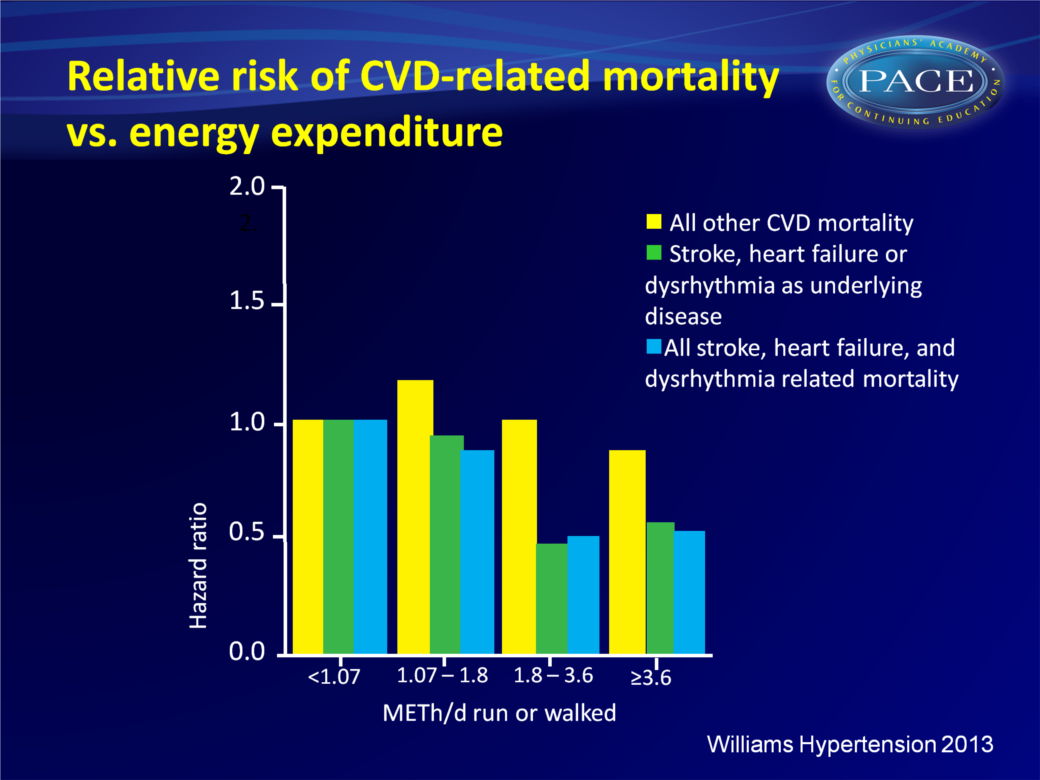

- Concerning CVD-related mortality, exercising at 1.8-3.6 METh/d gave a 34% decrease, which persisted at greater energy expenditures. Adjustment for BMI did not change the results.

- Other CVD end points such as cerebrovascular disease-related, heart failure related and dysrhythmia-related mortality showed stronger reductions in risk at >1,8 METh/d than <1.8METh/d. Risk of ischemic heart disease-related mortality per METh/d was less affected by energy expenditure, and hypertensive heart disease-related mortality was unrelated to exercise energy expenditure.

- Each METh/d increment in energy expenditure was associated with 19.1% lower risk for diabetes-mellitus-related mortality, which persisted when adjusted for BMI.

- Risk of CKD-related mortality was also reduced by 25.4% per METh/d.

- Being a runner or a walker did not significantly affect the risk for all CVD-related deaths, at 1.8-3.6 or >3.6 METh/d, neither for individual CVD endpoints. Neither did exercise mode significantly affect the per METh/d declines in diabetes-mellitus-related or CKD-related deaths.

Conclusion

Exercise can reduce the hypertensive’s risk for cerebrovascular disease, heart failure and cardiac dysrhythmias. Risk reductions were larger than those reported before; this could mean that hypertensives profit more from exercise than others, or it could be due to this specialised study design.These findings suggest that current exercise guidelines are not adequate to significantly reduce CVD mortality. Reduction in mortality was achieved when exercising a bit more, to wit between 1.8 and 3.6 METh/d, at which individuals taking antihypertensive medication are at the same risk level as sedentary nonusers.

Provided the energy expenditure is the same, walking and running yielded similar risk reductions. This means that one must go about twice as far and long to expend the same amount of energy by walking briskly as by running.

References

1. Rossi A, Dikareva A, Bacon SL, Daskalopoulou SS. The impact of physical activity on mortality in patients with high blood pressure: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1277–1288.

2. Williams PT. Relationship of distance run per week to coronary heart disease risk factors in 8283 male runners. The National Runners’ Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:191–198.

3. Williams PT, Franklin BA. Reduced incidence of cardiac arrhythmias in walkers and runners. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65302.

4. Williams PT. Vigorous exercise, fitness and incident hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:998–1006.

5. Williams PT. Advantage of distance- versus time-based estimates of walking in predicting adiposity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:1728–1737.

6. Williams PT. Non-exchangeability of running vs. other exercise in their association with adiposity, and its implications for public health recommendations. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36360.

7. Williams PT. Distance walked and run as improved metrics over timebased energy estimation in epidemiological studies and prevention; evidence from medication use. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41906.

8. Williams PT, Thompson PD. Walking versus running for hypertension, cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus risk reduction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:1085–1091.

9. Williams PT. Reduced diabetic, hypertensive, and cholesterol medication use with walking. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:433–443.

10. Williams PT. Reductions in incident coronary heart disease risk above guideline physical activity levels in men. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:524–527.